Click here to sign up!

You’ll be the first to know when I write something new, get access to exclusive free short stories and character profiles, get access to new artwork and photography, and free access to my essays!

You’ll be the first to know when I write something new, get access to exclusive free short stories and character profiles, get access to new artwork and photography, and free access to my essays!

148 Years ago:

January 15th, 1778

The sergeant was back.

Benjamin Hazard pressed his forehead against the window frame. His breath melted a hole in the frost, showing the sergeant’s red coat that stood out against the gray morning at the corner of Thames Street and Bannister’s Wharf. Same position as yesterday. Same as the day before.

This morning the sergeant held a notebook.

Benjamin pulled back from the window. His feet found the cold floorboards. He reached for his stockings and pulled them on. His mother had knitted them by candlelight after the store closed. The yarn was rough but warm.

Downstairs, his father, William, sat at the desk beside the counter. Lines had carved themselves deep around his eyes these past two years. When he looked up, his smile didn’t reach those eyes.

“Fourteen years old today,” he said quietly. “Hard to believe.”

“That sergeant’s watching again.” Benjamin kept his voice low. “Same spot. He’s taking notes this time.”

The pen stilled against the page. “You’re certain?”

“He’s not hiding it anymore.”

The back door opened. Cold air came in with his mother. She set down her armload of wood. Her face was tight, as if she were waiting for bad news. She saw Benjamin and her face changed. She crossed the room and pulled him against her. He was much taller than her now, and he bent down to embrace her. He could smell soap and wool and something else that meant safety in an unsafe world.

“Happy birthday.”

“I smell molasses.”

She pulled back while holding onto him with her hands. Her eyes held a gleam that seemed to say that she’d already won an argument that hadn’t happened yet.

“Do you now? What makes you sure that this has anything to do with you?”

“Hope.”

“Hope springs eternal,” she said, smiling at him warmly.

“Thank you, Mother,” he said, giving her one final squeeze.

“If someone’s making birthday cornbread while British soldiers count our windows,” his older sister, Bridget, called from upstairs, “I’m coming down.”

His father looked up at the ceiling. “Your sister can smell trouble and molasses from equal distances.”

“Both useful skills,” Bridget said. They could hear her feet hitting the floor.

***

His mother went to the hearth and returned with cornbread. She cut it with the careful precision she’d learned as an indentured servant—the same precision that had carried her from bondage to merchant’s wife. His father took his piece and looked at it.

“The good molasses.”

“Yes.”

“We could have sold it for actual coin.”

“We could have.” His mother sat down. “But if we’re arrested today, and we might be, given that sergeant’s attention, I want our son to remember we chose to celebrate him even when we knew danger was coming. That’s the memory that will sustain him through whatever follows.”

His father smiled despite himself. “Your mother has a gift for making principle sound like strategy.”

“That’s because it is.” She broke her own piece of cornbread. “It’s the same reason you bought out my indenture contract when you barely had money for your own store; the same reason we don’t sell to the British commissary even though they pay premium prices; the same reason Thomas stopped speaking to us after we publicly became abolitionists, when his wealth depends on the slave trade. Principle isn’t complicated; it’s just expensive.”

Bridget came down the stairs and took a piece of cornbread. “If we’re going to be poor and principled, at least we’re well-fed today.”

Benjamin watched his parents look at each other—wordless communication that came from years of facing the world together. His father’s hands shook slightly as he broke his cornbread. His mother’s accent was getting thicker. It always did when she was afraid.

“Three days of watching,” his father said quietly. “And now he’s taking notes. That’s not casual patrol.”

His mother’s fingers stopped moving. “Do we need to—”

“What? Run? We’re merchants. We sell provisions. We haven’t done anything wrong.”

“Thomas stopped by last week,” Bridget said. She had a thoughtful look on her face. “Asking about our suppliers and our delivery schedules. I thought he was just making conversation.”

The temperature in the room dropped.

“Why didn’t you mention this before?” his father asked.

“Because I thought I was being paranoid. But now …” She gestured toward the window where the sergeant stood watching. “Now I’m not so sure.”

***

As they cleaned up from breakfast, the front door opened, and its bell chimed. Too early for customers. Too early for anything good.

Duchess Quamino came in with her basket of pastries. She was a slave of the Channing family, but was allowed to run a small catering business in which she would share the profits with her master. She was also a good friend to the Hazards. The smell of cinnamon and nutmeg filled the store. Her presence brought warmth that pushed back against January’s bite and something else: a grinding fear.

“Benjamin Hazard.” Her voice carried strength that belied her circumstances. “Fourteen years today. That deserves proper recognition, even in times like these.”

She produced a cake wrapped in clean linen. Frosted plum cake that had made her famous among Newport’s elite. At a time when sugar had become more valuable than silver, this represented extraordinary sacrifice—ingredients she could have sold for desperately needed coin, choosing instead to celebrate a boy’s passage toward manhood.

“Duchess, you shouldn’t have—” his mother began.

“Birthdays matter.” But something brittle lived underneath the warmth now, something that hadn’t been there six months ago. “Besides, Mistress Channing ordered extras for a gathering that was postponed. Better to share joy than waste good ingredients.”

She arranged her remaining pastries on the counter with practiced efficiency, but her hands trembled. When his mother moved closer with the instinct of one woman recognizing another’s distress, Duchess’s composure wavered.

“Had word from John three days ago,” she said quietly, glancing toward the door to ensure no customers were approaching. “He’s well, praise God. His captain treats his crew fairly, pays them proper shares. But every day he’s at sea is another day I wake wondering if this is the day I get different news.”

“John’s smart and capable,” his mother said. “He’ll come home.”

“Will he?” Duchess’s hands stilled on the pastries. “Every prize he takes at sea is blood money, Mary. Money to buy what shouldn’t need buying. Our freedom.” Her voice dropped even lower. “Charles asked me last night when Papa’s coming home. He’s six years old. How do I explain that his father is risking his life privateering to earn money to purchase his own family? That we might lose him trying to win our liberty?”

She pressed her fingers against the counter, and Benjamin saw the cost of maintaining her dignity every day: serving people who saw her children as property, smiling through the fear that gnawed at her every waking moment. Her husband, John Quamino, had won enough money in a lottery several years ago that he was able to purchase his own freedom. But he worked in one of the only positions that a free African man had where he had the opportunity to make enough money to buy the freedom of his family.

“If he doesn’t come back …” She couldn’t finish the thought. “I’ll have to find another way. Years more of bondage while I scrape together coins from frosting cakes for men who think I should be grateful for the opportunity.”

His mother reached out and squeezed her hand. For a moment, two women who had both known bondage—one through indenture, one through slavery—stood together in silent understanding of costs that free people could never fully comprehend.

Duchess straightened, forcing brightness back into her voice. She focused on Benjamin again. “Use this year wisely, young man. These are times that forge character. What we become in darkness reveals who we truly are.”

After she left, Benjamin stood holding the precious cake, understanding he’d received more than a birthday treat. Her courage was something he was only beginning to comprehend.

“She’s remarkable,” he said quietly.

“She is,” his mother agreed. “And John Quamino is braver than most who call themselves soldiers. Fighting for your family’s freedom when the law says they’re not even yours to fight for—that takes a kind of courage I can barely imagine.”

***

Benjamin went to the backyard to split wood. January air bit at his exposed skin. He positioned a log on the chopping block and raised the axe, but movement through the gap between buildings caught his eye.

A figure in a heavy woolen cloak stood against the brick wall of the warehouse on Bannister’s Wharf, two blocks distant. Not watching the way the sergeant had watched; this was different. The man’s posture suggested alertness, readiness. As if he were standing guard rather than gathering intelligence.

Benjamin brought the axe down. The crack echoed between buildings.

When he looked up, the figure had shifted position but remained visible; deliberate, as if he wanted to be seen but not identified. The cloak’s hood shadowed his face, but something about his bearing suggested strength, competence, protection.

Benjamin split another log. The figure still watched.

He stacked the wood carefully, his mind racing. Two different kinds of watchers: the sergeant’s obvious surveillance, building a case against them, and this other presence that felt like a guardian angel hiding in shadows.

He didn’t know which frightened him more.

***

When he came back inside, stamping snow from his boots, the bell chimed again.

Newport Gardner entered, moving with the careful dignity of a man who understood exactly how much space he was permitted to occupy in the world. His fingers tapped complex rhythms against his leg as he approached the counter, unconscious, like a musician hearing melodies no one else could detect.

“Mr. William, Mrs. Hazard.” His voice carried the musical cadences of the Gold Coast, vowels that rose and fell musically. “Young Benjamin. Fourteen years today.”

He paused. Those restless fingers still tapping. “The same age I was when I was taken into Master Gardner’s household.”

His father was already gathering supplies: flour and salt for Newport’s master, the familiar rhythm of their unspoken arrangement. “What brings you out so early?”

“Master Gardner is planning a reception. British officers want everything proper for an important visitor arriving next week.”

Newport’s voice remained carefully neutral, but his eyes flicked toward the windows, checking for observers. “They discuss such things freely while I tune the harpsichord. A musician becomes invisible while visible.”

He moved closer to the counter. His voice dropped to barely above a whisper. “But mostly I came to share word. Mrs. Tillinghast stopped me on Thames Street this morning. She’d heard a newly arrived sergeant has been asking questions about specific families. Yours among them. Detailed questions: delivery schedules, customer lists, and family connections. She thought you should know before the day’s business begins.”

“Any idea what prompted this interest?” his father asked, equally quiet, his hands continuing their work—the performance of normalcy that had become survival in occupied Newport.

Newport accepted the package his mother offered. He paused. “Major Ashworth told Master Gardner that the new provost sergeant has a particular talent for identifying ‘merchant families who hide their sympathies behind commercial neutrality.’ Those were his exact words. And then he mentioned your name, Mr. William, along with two others. The Overings and the Robinsons. Both have already been visited by soldiers this week.”

His father’s hands stilled on the package he was tying off. “I see.”

Newport lifted the smaller bundle his mother had prepared—cornmeal for Johnnycakes, one of her “extras” that had become legendary among Newport’s struggling households, distributed without regard to the color of the recipient’s skin. A dangerous kindness in a city where such things were noticed and remembered.

“Much obliged, Mrs. Hazard. My master will appreciate the quality of your goods as always. I will appreciate the johnnycakes.” He paused at the door, glancing back to ensure no one was within earshot on the street. When he spoke again, his voice carried something more personal, more raw. “Be careful today. All of you. When provost sergeants take notice of you, they already know what they’re looking for. They’re just building the case to make the arrest look proper.”

After he left, silence hung heavy in the store.

“The Overings and the Robinsons,” his mother said quietly. “Both had soldiers search their premises this week. Both were questioned about their suppliers and associations.”

“And both were released without charges,” his father said, but his voice carried no relief. “Which means either they satisfied the British or—”

“Or they’re building toward something bigger,” Bridget finished from her position near the stairs. “Using the smaller fish to catch the larger ones.”

Benjamin stared at the door Newport had just exited. “Why did he risk coming here? If they’re watching us, if they’re building a case—”

His mother was wrapping the extra cornmeal with trembling hands, her movements precise despite the fear. “Because some gifts are dangerous to give, love. Especially for those who have so little freedom to give anything at all. What he just did—coming here, warning us when he could be seen—that’s trust. The kind that could cost him everything.”

She looked at Benjamin. “Remember that. Remember who risks what, and for whom. That’s the measure of a person—what they’re willing to sacrifice for others when they have so little to spare.”

***

The morning brought a trickle of customers. Each one carried fragments of disturbing news woven into ordinary transactions.

The door opened again. Joseph Wanton entered. His boots clicked against the floorboards with the precision of a man who expected the world to accommodate his presence.

The former governor’s son carried himself with rigid authority. He was a fierce loyalist, although many felt only because his shipping business relied on the British Navy’s protections. His pale eyes scanned the inventory with the assessment of someone cataloging assets.

“William. I require candles. Good ones, not the tallow drippings most establishments are reduced to selling.”

Benjamin’s father gathered beeswax candles. Wanton examined them with expert fingers that had once managed one of Newport’s most successful merchant houses.

“These are actually quite fine. Better than Robinson’s been offering the garrison.” The admission seemed to irritate him. “Thomas speaks often of how family names once commanded universal respect in Rhode Island. Such a pity when certain branches choose questionable associations.”

Benjamin caught the emphasis on ‘Thomas.’ His father’s cousin. Who had always treated their family with barely concealed contempt. Who had stopped by last week asking about their suppliers, their schedules.

“How many will you need?” his father asked, voice carefully neutral.

“A dozen. Major Ashworth appreciates proper illumination during his correspondence. General Pigot has given him considerable latitude in security matters, and he writes extensively about Newport’s remaining challenges.” Wanton’s gaze swept across the family, lingering on each face as if memorizing them. “Thomas has provided Major Ashworth with considerable insight into Newport’s social dynamics. The Major values such civic cooperation.”

He counted out coins with deliberate slowness, each clink against the counter like a small verdict. “The Hazard name still carries weight, William. I trust you’ll remember that when difficult decisions must be made about family loyalty.”

He paused at the door. “Those candles truly are exceptional quality. Whatever else I think of your choices, you’ve never compromised on merchandise. I do hope you’ll remember that reputation matters, even in difficult times.”

After the door closed, the store felt poisoned.

“He knows,” Bridget whispered.

“Knows what?” his father asked, though his face had gone pale.

“Whatever’s about to happen. That wasn’t a threat. It was a farewell. He was saying goodbye to the store, to the merchandise, to …” She gestured helplessly. “To the way things used to be.”

They didn’t have long to wait.

***

The front door crashed open. It bounced against the wall hard enough that dust scattered from the impact and a small crack appeared in the plaster.

A tall blond lieutenant strode in with two privates flanking him. He stopped in the center of the room with military precision, boots planted, shoulders back; every inch of him radiating the authority of His Majesty’s armed forces.

“Lieutenant Reginald Fairfax, by order of Major Ashworth. This establishment is subject to immediate search for seditious materials.”

His Virginia drawl was sharp. Everything about his bearing spoke of gentry who saw the Revolution as mob rule, who believed order required hierarchy and hierarchy required force.

Behind him came the sergeant Benjamin had been watching for three mornings. He moved with predatory grace, carrying the rough authority of a man who had earned his rank through twenty years of service rather than purchase or family connection. His pale green eyes swept the store, cataloging details he’d clearly studied during his surveillance.

“Sergeant MacReady,” Fairfax said. “Search the premises. Thoroughly.”

“Of course, Lieutenant.” Highland accent, rough as granite. MacReady’s gaze settled on Benjamin for a moment, assessing, calculating, then moved on.

“How may we assist?” William stepped forward. His hands were visible and non-threatening, the posture of a man who understood that cooperation was survival.

“Through silence and cooperation.” Fairfax’s gaze found Benjamin’s mother. Lingered with calculated insult. “Mrs. Hazard. Irish-born, I understand? Catholic? Known abolitionist sympathies? I trust you understand the importance of demonstrating proper loyalty to legitimate government, particularly given your … background.”

“We serve Newport’s residents according to our conscience.” His mother’s voice stayed level, but her Irish accent was thickening.

“Conscience doesn’t supersede lawful authority, Mrs. Hazard. These are dangerous times for philosophical luxuries.” Fairfax gestured to his men with sharp precision. “Sergeant MacReady, search everything.”

MacReady gestured to his men with crisp efficiency. “Grimsby, Morrison, search the premises.”

The two privates moved through the store like locusts, overturning crates and barrels that represented the family’s survival, scattering merchandise across floorboards with aggressive enthusiasm.

Private Morrison—thick-set with scarred hands and the build of a man who’d spent his life doing hard labor—worked his way toward the back with focused attention. He wasn’t searching randomly. He moved with purpose, ignoring some areas entirely while focusing on others with careful attention.

Bridget caught it before anyone else. She’d been watching from the stairs, her sharp eyes tracking Morrison’s progress. “He knows where he’s going,” she whispered to Benjamin. “He’s not searching. He’s retrieving.”

Benjamin watched Morrison’s progress with growing dread. The private moved past crates of salt pork, barrels of flour, shelves of candles and soap. All the places you’d hide something if you were actually hiding something.

He went straight to the wooden crate marked “CORNMEAL – BOSTON” in black stenciled letters.

Didn’t hesitate.

Grabbed the crate.

Hurled it against the wall with deliberate force.

The impact jarred the lid loose, a sharp crack that echoed through the store like a gunshot.

White cornmeal spilled across the floor in a cascade of pale grain.

And something else.

Papers scattered like fallen leaves, covered with columns of numbers and letters arranged in careful patterns that clearly represented some form of code.

Benjamin stared at the documents. The crate had arrived yesterday; he’d helped unload it himself, but something had been wrong. The weight when he’d lifted it. The way it had settled unevenly when they’d set it down. At the time he’d thought the cornmeal had shifted during transport.

Now he understood. Someone had opened it. Added those papers. Resealed it so carefully he hadn’t noticed.

It was someone who knew their routines intimately, someone who had access to their suppliers, their delivery schedules, and their inventory management.

MacReady was beside the spilled crate in two quick strides. He lifted the sheaf of papers from the pile of cornmeal on the floor with careful attention, holding it up to the lamplight.

“Coded communications, hidden in routine supplies with systematic care. This suggests regular intelligence operations, not isolated incidents.”

“I’ve never seen those papers before.” Benjamin’s father’s voice cracked with genuine bewilderment. “I don’t know what they are or how they got there.”

“Without your knowledge?” MacReady’s eyebrows rose with practiced skepticism. “In your own store? In a crate that arrived under your supervision yesterday?”

“Yes. I don’t know how they—”

“Perhaps you’re simply more clever than most traitors, Mr. Hazard. Or perhaps you’re telling the truth and someone has been very helpful in ensuring these documents found their way to your establishment.” MacReady examined the papers more closely, his rough fingers tracing the coded text. “Either way, the evidence speaks more clearly than protestations. These aren’t amateur scribblings. This is professional intelligence work.”

MacReady flipped through the pages. The top few were formatted like a ledger, in carefully drawn block letters. But the contents of the ledger were not words, they seemed encoded by some cipher. Then he found one that wasn’t enciphered; he studied it carefully.

Benjamin caught sight of the handwriting. Not printed, not anonymous, but careful script that he’d seen on invoices, correspondence, documents that had passed through their store regularly over the years.

His hands went numb.

The room tilted slightly.

He tried to speak but his throat had closed.

The handwriting was Thomas’s, his father’s cousin, who had always treated their family with barely concealed contempt, who had stopped by last week asking about their suppliers, their delivery schedules, and who moved in Joseph Wanton’s circles and had access to their store, their routines, their vulnerabilities.

Benjamin looked at his father. His father hadn’t seen it yet. Didn’t know what Benjamin knew, still thought this might be some terrible mistake that could be explained, corrected, survived.

Morrison produced iron shackles with casual efficiency. The metal gleamed dully in the lamplight, catching and reflecting the morning sun that streamed through the windows.

“William Hazard, Mary Hazard, you are under arrest for sedition and conspiracy against His Majesty’s government.”

Benjamin watched the shackles close around his father’s wrists. The sound they made: metal clicking into place, the slight rattle of chain. The iron was cold enough that his father’s wrists jerked back involuntarily, but Morrison’s grip was stronger.

Iron closed around his mother’s wrists next. Mary Sullivan Hazard, who had arrived in Newport as an indentured servant and built herself into a respected merchant’s wife through intelligence and determination, who had convinced his father to avoid the slave trade even when it meant they lived one step closer to poverty, and who had organized women for boycotts and operated as a message center because she could read when many couldn’t.

“Please.” Benjamin heard his own voice though he hadn’t planned to speak. “They’ve done nothing wrong. We’re just merchants trying to survive.”

“Just merchants don’t hide coded intelligence in their inventory.” MacReady studied the papers with professional interest. “Evidence speaks clearer than protestations, boy. Your parents have been running intelligence operations for months, perhaps years. These documents prove systematic coordination with rebel forces.”

Fairfax smiled with cold satisfaction. “The children will be detained as material witnesses. Their interrogation regarding their parents’ activities will be comprehensive and thorough. Major Ashworth has particular interest in understanding how long this operation has been functioning.”

The word ‘interrogation’ hung in the air, carrying implications that made Benjamin’s blood turn to ice.

MacReady examined the coded papers once more, then made his decision. “Lieutenant Fairfax, I recommend we arrest the children as well. Material witnesses to their parents’ activities. Children often remember details their parents think they’ve hidden. Their testimony will be valuable during examination.”

Benjamin’s mother had remained controlled through the search, the destruction, even her own arrest. But when she realized her children were about to disappear into British custody, something broke.

She didn’t scream.

She went cold.

When she spoke, her voice carried sounds Benjamin had never heard from her before: words that weren’t English, weren’t anything he recognized.

“Ná bain dóibh, le do thoil. Tá siad óg. Níl a fhios acu faic.”

Then English, but the accent so thick it was almost another language, the accent of her childhood before she’d learned to control it for Newport society: “They’re only children. Whatever you think we’ve done—whatever someone has told you we’ve done—they had no part in it. They know nothing. Please. Le do thoil. Please. They’re too young for this. Benjamin is only fourteen.”

Morrison’s hands hesitated on the shackles. Private Grimsby glanced at Fairfax as if seeking permission to feel human.

But Morrison continued his advance methodically. The shackles gleamed in the lamplight as he moved toward Benjamin and Bridget.

Benjamin stared at those papers in MacReady’s hands. Thomas’s handwriting: his cousin’s careful script on documents that would destroy them all. His father still hadn’t seen it. Still didn’t understand who had betrayed them. Still thought this might be some terrible mistake.

This wasn’t random. This wasn’t accident. This was family deciding that the broader Hazard name mattered more than this branch’s survival. Thomas choosing his social position over their lives.

The shackles gleamed as Morrison reached for Benjamin. Bridget stepped forward instinctively, placing herself between her younger brother and the soldier: a protective gesture that earned her a warning look from MacReady.

Through the window, Benjamin caught a glimpse of that cloaked figure from the alley. Still watching. Still waiting.

But for what?

The story continues in Episode 2. “The Magnificent Rescue”

Access more Episodes here:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0G3XYC8JK

Copyright Eric Picard – 2026

I remember reading that 19th Century authors, like Charles Dickens, published some of their most famous novels serially in newspapers and magazines. Dickens is rather famous for it, but I’ll bet many people don’t know how common this was, and also what great works of literature were published this way.

It turns out an astonishing number of literary giants published some of their best known works in monthly or weekly installments. It’s incredible to realize that Tolstoy rolled out War and Peace this way. Dostoevsky published Crime and Punishment chapter by chapter. Even Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories were published this way. Alexandre Dumas serialized The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo.

Wilkie Collins, Thomas Hardy, Victor Hugo, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Henry James were doing the same. Imagine reading War and Peace one chapter at a time for months and months (and months.)

If it was good enough for them, well…

So here’s my experiment. If I follow in the modern footsteps of Hugh Howey, will people read my work? I hope so.

The first two episodes of The Hazard Trade are now live on Amazon’s Kindle store. Every month or so you’ll be able to read the next installment. You can read Kindle books on literally almost every device – including a web browser. So don’t fret if you don’t have a Kindle Reader Device. I read all my books on my phone (with the font size UP and the background Black with White Text) using the Kindle Reader app.

Since these are such small time investments, each chapter is aiming between 7,000 and 10,000 words (to make the investment worthwhile) at $0.99 a pop – I hope you’ll give it a whirl.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0G3XYC8JK

I’m aiming to publish these monthly, and since I’m writing as we go, you have a great opportunity to give me feedback as we move forward. And as always – the best gift you can give to an author is a positive review on Amazon and Goodreads. I hope you’ll enjoy.

Please join my newsletter to get automatically informed each time a new episode is published: https://newsletter.ericpicard.com

Eric

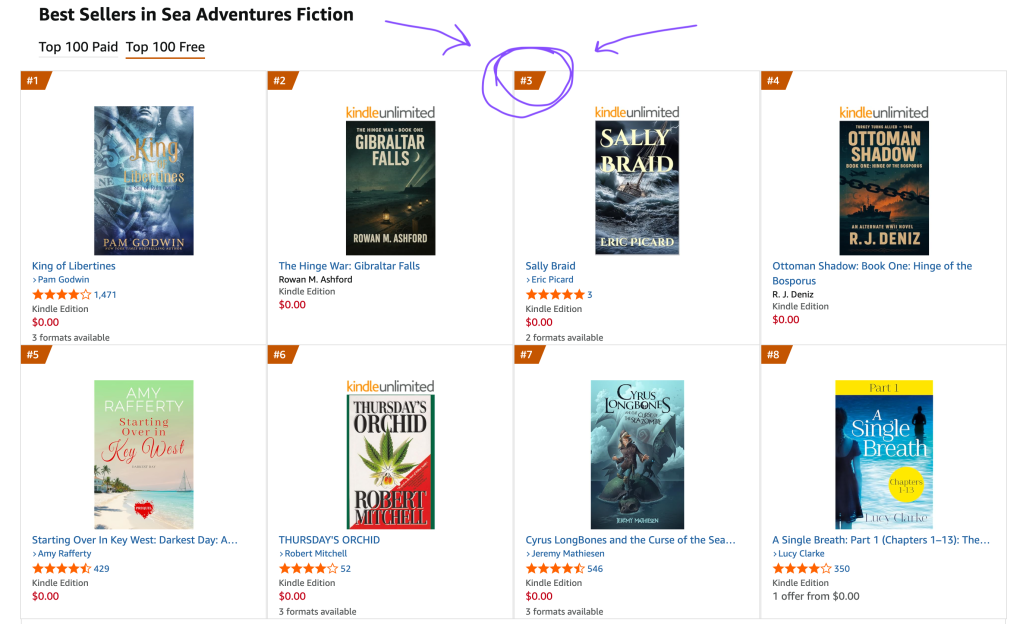

My short story, Sally Braid is free on Amazon for ONE MORE DAY!

Please get your free copy now. It hit number 3 in Sea Adventure Fiction today. And you can add an audiobook version for just $1.99!

I wrote the first version of Sally Braid in graduate school, and rewrote it just a few years ago. Below is the new Afterword that I just added to it, should be live in the eBook version later today or tomorrow.

—

I had been a commercial boat captain during the summers, all through college and graduate school. I drove launch tenders, boats that take people from shore out to their boats on moorings and anchors, in Newport, Rhode Island. The launches were 26 feet long, could take about 20 passengers. It was an amazing summer job, one where I learned not only how to handle boats incredibly well, but where I learned a lot about people. I drove the launch in all sorts of conditions, including once in a hurricane (without any passengers.)

One night in early September before going to graduate school, I was tied up at the dock while an unforecasted squall came through, much like what Tess experienced. During the peak of the storm, with lightning striking all around the harbor, I got a call on the radio from the Harbor Master. He was trying to rescue a boat that had broken loose when the squall line came through. He was a young guy, a junior Harbor Master, and had very little experience towing boats, and was getting dragged towards the rocks at the Ida Lewis Yacht Club. I reluctantly left the dock in 50 knots of wind, with driving rain, lightning and thunder going off all around me.

It was the first time in my life that I was so close to lightning strikes. The hairs on my arms were standing up with static electricity just before the lightning strikes. The air was lasing purple, and I saw St. Elmo’s Fire, the corona effect ahead of lightning strikes, on tall boat masts around me. The sound of the thunder was so loud that I felt it in my chest, the only other time I’ve felt anything like that was being close to fireworks going off. I imagine it must be similar to be in artillery fire. My 57 year old brain thinks my 23 year old self was a moron for going out, but the memory of the panicked, pleading sound of the Harbor Master’s voice reminds me that I needed to go.

When I got to the Harbor Master, he had caught a 70 foot classic wooden yacht that had broken loose from its mooring. He had tied off too far forward on the boat and couldn’t stop it from dragging. I tied off properly on the other side of the boat, and I got the yacht under control. As I tied the launch off, a wave came up and went right down the front of my foul weather gear, and my only thought was that the ocean water was so warm, much warmer than the air and rain.

We got the boat across the harbor and tied off on another mooring. The Harbor Master thanked me and said he owed me a beer. I told him he owed me his firstborn child.

Tess is an amalgam of several of my customers, but two in particular. One was a woman who was as hard as nails, an avid sailor who had Olympic aspirations in her twenties, but never made it. She sailed with her husband on their yacht, racing all over New England. Everyone thought it was her husband who was the great sailor, and they won a lot of races. In reality, while he ‘drove’ the boat, it was his wife who was the tactician and navigator, and really ‘ran’ the boat. I asked her once if it bothered her that nobody realized that she ran the boat, and she smiled an uncharacteristic smile, but didn’t answer. They were in their fifties, about my parents’ age at the time. To me they were an older couple, but were actually younger than I am right now. Time changes perspectives.

I had another customer who was Tess’s age, in her seventies, who had lost her husband the previous year. She had spent decades on their boat, a classic wooden trawler, which her husband had meticulously maintained. But she herself always relied on her husband to take care of everything. She barely knew how to drive the boat, and didn’t know how to turn on the engines, run the generator, didn’t understand about bilge pumps, charging the batteries, or that the refrigerator on her boat shouldn’t be left on while on the mooring without shore power.

One night when I was driving by, I noticed that the boat was very low in the water. I knocked on the hull and she came out. We realized the batteries were dead, and the bilge pump was not running. Like many old wooden boats, she had a tiny leak around the shaft that the bilge pump normally kept up with easily. But since the batteries were dead, the pump wasn’t running and the boat was slowly sinking. I helped her start the generator, and showed her how the different battery switches controlled where the power went, from which batteries. All very mundane stuff, but rather critical to understand when living on a mooring.

She was very sweet and sad, and the launch drivers took her under our wing and helped her out with everything. By the second week on the mooring she had learned every hard lesson she needed to learn about what not to do. Undaunted, she stayed on the boat all summer long, into the Fall. She slowly became more confident. One evening when it was very quiet and slow, she invited me swing by for dinner and I tied the launch up next to her boat and we talked for a bit.

As we ate, I asked her why she’d decided to stay on the boat that summer, and she got very quiet, and shyly said, “It’s the only place I still see him.” The hairs on my arms went up, just like they did that time from St. Elmo’s Fire.

I’m so excited to tell you about the new audiobooks I released this week. You can get audio versions of any of my books via Amazon or Audible.

Legacy of the Bitterroots is below:

https://www.audible.com/pd/B0FP5RT618?source_code=ASSORAP0511160006&share_location=pdp

Giveaway ends September 17, 2025.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

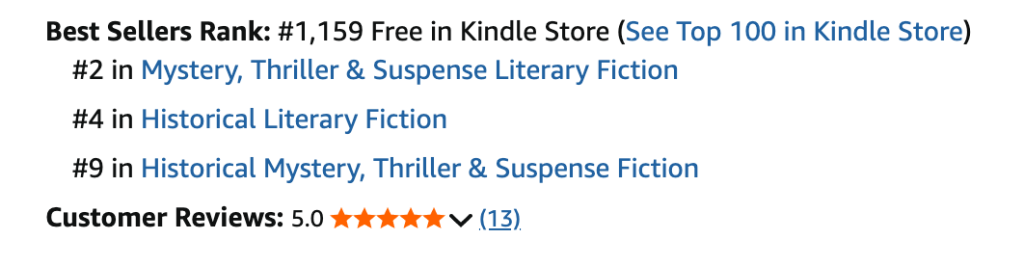

“Legacy of the Bitterroots” is doing really well on Amazon Kindle right now. Since it’s available this week for free as an eBook download, I’m in a special category “Kindle Free Store”.

I’m #2 in Mystery, Thriller & Suspense Literary Fiction, #4 in Historical Literary Fiction, and #9 in Historical Mystery, Thriller & Suspense Fiction.

It would be awesome if I was at those numbers outside of the “free” category! But I’ll take it as it comes! Thanks to everyone who has taken advantage of the free download. And if you haven’t, please do so this week before the price goes up to $5.99. This is in celebration of the launch of the print book, which went live on Monday.

Also – if you like it, please, please do give it a review. The best way to help a debut author is to give it a “Purchase Verified” review of the book. I’m at 13 5-star reviews. If I can get to 25 things get really interesting. Any help deeply appreciated!

Yay for this small win! I’ll take it!

Legacy of the Bitterroots

Picard, Eric

(NOTE: READ THIS! Ingram Spark, who powers this link, requires that you place a “+1” ahead of your phone number on the order form. I’ve filed a bug report, hopefully they fix this. But to order the book on this link, you’re required to put in your phone number, and you must put your country code (US = +1) into the phone number form field.)

Get it here as an eBook download on Kindle: https://a.co/d/eUpq4d9

I stayed up for several nights working on the cover design. Once a designer, always a designer, I guess. I’m disproportionately pleased with the way it came out.

I lost days of sleep over the last few months working on the manuscript with my editor, Andy. He kept finding places where I hadn’t invested ahead of time in the payoff. The backstory was clear in my head, but hadn’t made it onto the page.

Many times writing this novel, I felt chills. A few times I teared up. But going back to write a few of these earlier scenes after the fact, I broke down sobbing. That’s when I knew the characters had become real for me.

I started writing this book—actually writing words—in 2020 when I found myself unemployed during COVID. The two job offers I’d been verbally given the same week, March of 2020, evaporated as the world suddenly realized how screwy things were going to become.

I started working on this book way back around the turn of the century. I’d awoken from a dream. I’d been hiking in the woods and come across a village from the turn of the previous century, abandoned but perfectly preserved.

As I wandered the village, looking into abandoned and dusty storefronts filled with unsold goods, I wondered what had happened. A man hailed me from the distance. He was elderly. He was the caretaker of the village and welcomed me. He said he’d inherited it from his father, who’d inherited it from his father before him. That it was a boom town during a gold rush, but that when the gold played out, the people left.

I woke up confused. And intrigued. It was one of those dreams that really stuck with me, fishing hooks firmly embedded in my brain. I started thinking about how a perfectly preserved village like that could be turned into a theme park of some kind. I called my friend, Gary, who was working at Disney, and we talked about the idea for several hours. I was enthusiastic and excited but felt weird, like Gary must have thought I was nuts. He played along, at the very least.

I kept thinking about this idea over the years. I’d written most of a novella in graduate school—80 pages or so falling out of me like water from a hose. But I felt like it was too derivative and abandoned it for 30 years. That novella became Frost, which I published last year after dusting it off and rewriting it.

I knew I was capable of writing a novel. I’d written several short stories, plus the unfinished Frost. But if I was going to take time off from a busy career and family to write a novel, I was going to really put in the work. I just never felt like I had the time or extra energy I knew it would take to turn this idea into a novel.

Years went by.

In 2016 I was driving across the country with my wife. We were on the highway in Montana, and a small sign caught my attention. It read “Garnet Ghost Town” with an arrow pointing to a dirt road off the four-lane undivided highway.

I pointed it out to Erynn, and she said, “Let’s do it.” I almost flipped the Honda Pilot, turning onto the dirt road at highway speed. We drove into the woods for way too long. Every time we got to the point of giving up, we’d come to a crossroad that had another sign. After almost an hour, thinking we were driving into a trap set by meth-heads, we came upon Garnet. It’s amazing. The best-preserved ghost town in the U.S., according to their sign.

We spent a few hours wandering Garnet. It’s truly incredible. And right then, the novel went beyond fishing hooks and was metaphorically more like a bone graft.

Years went by.

I was introduced to Hugh Howey by a mutual friend. I’d read his book Wool and was a huge fan. Hugh hosted a meetup in Seattle, where I lived at the time, for writers. I went, even though I hadn’t written anything besides a few hundred trade articles and some essays in previous decades. Hugh was very gracious, despite my fanboy intrusion amongst the working writers.

We connected—at least I connected—over a shared background working in our 20s as boat captains. He’s a bit younger than me, but our timeframes overlapped, and we knew a few people in common.

When he asked what I was working on, I gave him my job description. He laughed. He said, “No, what are you writing?” I was a bit embarrassed. I explained that while I was writing hundreds of pages of content a month, most of it was strategy or vision papers and product specifications. And the rest was trade articles. I was writing two monthly columns at the time.

He looked a bit uncomfortable, and I said, “Well, I have a mostly finished novella that I started in grad school. And I’ve got this crazy story that’s had its hooks in me for years, and eventually I’ll write it.”

He looked both relieved and interested. “What’s it about?”

So I told him about it. He said something polite and, of course, encouraged me to write it. He was in high demand, and I’d taken up more time than I should have, and he was whisked off by another writer.

So a few years later, when I suddenly had some time, I realized there were no excuses. It was time to write the novel I’d been putting off for 20 years.

I quickly learned that my history degree was both a blessing and a curse when writing a historical novel. Frost fell out of me with very little effort—it was like breathing. Writing the historical sections of Legacy was a slog. I probably spent five to ten hours researching for every hour I wrote. It wasn’t unpleasant—I love researching history. It was, however, a lot of effort. Months were going by, and I was uncovering more historical mysteries and opportunities for every one that I incorporated into the story.

It felt like serendipity—and panic. I saw that the four months that I’d allocated to getting this book done were not going to be nearly enough. It makes me laugh to read that sentence right now, because I had so hilariously misunderstood how long this was going to take. The modern storyline was easy; I wrote each of those chapters in a day or two, but the historical sections were becoming interminable. I was a bit panicky because I needed to find a job. But COVID giveth and COVID taketh away, and I soldiered on.

Ultimately I was nowhere near done, stuck on the chapter where the executives from Yomohiro Corporation visited Idaho, when I did ultimately get a job. And things slowed way down. Each time I picked up the book, I had to reread what I’d already written to get back into the pace, and it was a self-reinforcing loop; as I wrote more, it took longer to pick the threads back up each time.

Finally, after more than two years, I had another break from work. I took that three months and made huge progress, but then got another job. Another two years, and I left that role and began consulting full time. This has turned out to be perfect, as I’m working about 50% of my time, and the rest has been used for writing and then editing.

This novel is a bit of a beast. It is a multi-generational saga that is nonlinear, meaning the modern story is interleaved with the historical story. I have a lot of literary friends, and a lot who are avid readers, so I got really valuable feedback from both groups. Some feedback that I got was that there were too many characters to keep straight. This was mostly because each of the stories had a full cast of characters, and the historical story stretched from 1867 to 1910 and involved founding and growing an entire village.

About eight months ago, I decided to disentangle the two stories and publish them as two linear books. So I dove into the historical story and treated it like an exercise in fleshing out a novel. There was a lot that it needed to stand on its own, and it was all valuable content that furthered the story.

I pulled in several new readers who had never touched the original interleaved story, and the feedback was universal that it was well written and a good story—but that it seemed like it was missing something important. And it was.

I’d never written the historical sections as a standalone—they were designed such that there was a slow build in the historical sections toward things that were revealed in the modern sections. Together, they were whole, but separately, they were incomplete.

I finally realized that there weren’t too many characters—at least not in service of the story I was writing. They just needed more room to breathe and to be complete beings. So in the exercise of writing each book to be standalone, I fleshed those characters out to the point where they were three-dimensional. And after a good friend—who had been an original reader, and then a reader on the standalone historical novel—told me he thought it needed to be welded back together…

By this point, the combined stories landed around 130,000 words. Which already is a lot. After a lot of thinking and discussions with other readers, I realized he was correct. And I welded the two stories back together.

I finally was at the point where I felt like the book was “done,” or at least whole. I reached out to a very close friend who is also a professional editor, Andrea Lorenzo Molinari. He had the time available to help, and he came on board as my official editor.

Andy is awesome. He was coming to this story—that I felt was complete—with fresh eyes. He started asking me some hard questions about various characters and scenes, and as we completed the first rounds of edits, I had a whole list of new scenes that needed to be added. Thanks be to Andy, because he was so right! The book really needed those additional scenes to be complete.

So that’s the whole story about the story—the saga of the creation of Crystal Village and the characters that inhabit the place. I hope you enjoy the book.

Today is July 4th, 2025 and the book went live on the 3rd as an eBook. The print release is waiting on me getting proofs back. If you want to read on paper, please keep checking back – and sign up for the newsletter, so you can get updates on availability. You’ll also get some free exclusive content for subscribers, and opportunities to weigh in on future books.

Below is a preview of my upcoming Novel, Legacy of the Bitterroots – A Crystal Village Tale. Please take a read, and I hope you’ll consider buying it when it is released.

The horse screamed. Artillery fire had torn open her belly. Her cry was not a whinny or a battle cry — it was like a woman’s shriek of agony. Through smoke-choked air, horses thrashed in blood-soaked mud, broken legs jutting at impossible angles, heads twisting as they writhed. One stood trembling, entrails hanging to the ground, steaming in the cold morning air. A dozen horses screamed across the battlefield, their combined agony drowning out the clash of bayonets and the shouting of men.

Hank jolted awake, his shirt soaked with sweat despite the mountain chill. He drew in the clean mountain air. It was crisp and fresh in his lungs, clearing the lingering stench of death. The screaming of horses was the worst sound he’d ever heard. Nobody spoke of it. Nobody could bear to. It was the true sound of war.

He shifted on the damp ground, heart still hammering in his chest, and tried to fall back asleep.

Hank wiggled his shoulder to find a spot without roots or rocks. He adjusted his blanket against the cold. Their hand-drawn map showed a few more days of walking to reach the claim. His brother Barney slept on the other side of the fire. They’d traveled five days out of Missoula Mills in Montana. The trip had been hard but beautiful.

They’d come west seeking gold at the invitation of childhood friend Joe Welch, who had served with them in the war. Joe’s package contained gold dust and a garnet the size of a man’s thumb, valued at ten dollars by their neighborhood jeweler. This wasn’t a gold rush or a stampede—Joe had found a secluded claim far from prying eyes. The claim sat a week’s hike beyond Missoula Mills, the last trace of civilization for a hundred miles. Joe had invited them and a few others to stake nearby claims. He sought companionship and safety. Though always jovial, he had wandered west after the war to quiet his demons. His letter arrived with an admonition of secrecy, and Hank agreed.

When the package from Joe arrived, Barney’s wife Madeleine pulled Hank into the pantry and clutched his arm.

“Hank, you know how he is. I dearly love the man, but he lacks the resolve to see such ventures through. I cannot bear the thought of him setting out without you by his side. He’ll charge ahead until he meets the first obstacle, and then return here, penniless and bereft of prospects,” Madeleine said, her eyes full of panic.

Hank sighed. “Maddy, I kept watch over him during the war, true enough. But he’s my elder brother, and I’ve not yet set my own affairs in order. I’ve no wish to embark on an escapade with Barney and Joe, only to find ourselves back here by autumn with nothing to show for it.”

Madeleine met his gaze with a fixed stare. “Hank. You are in disarray. You scarcely rest, barely eat, and you’ve grown gaunt. Chicago won’t mend what ails you. You need this more than Barney does. With you to guide him, I’m confident he’ll find his way back to me unharmed and with enough savings that we may cease relying on my father’s support. You may be a year his junior, but you are the steady hand we rely on. I beg you — go with him.”

Hank rolled onto his back and stared up through the pine boughs. The sky blazed with more stars than he’d ever seen in Chicago. The Milky Way flowed overhead like a river of light. He’d seen more shooting stars on this trip than in all his life. He and Barney had prepared well, pooling their resources to buy two mules and supplies in Missoula Mills. One mule pulled their two-wheeled pack cart; the other was heavily laden.

They’d served in the cavalry together — Hank as a Lieutenant, Barney as corporal. Hank had led his men to victory after victory, earning praise from command. But the war still gripped his mind — his days filled with a constant barrage of sounds, smells, and intrusive thoughts. Barney chattered endlessly about the war, as if only good memories had been created during their service. Hank had agreed to this journey hoping that distance might quiet his haunted sleep.

He rolled over, trying to sleep again. The next thing he knew, low morning light was in his eyes. Barney snored on the far side of the fire. A red squirrel sat on a branch, staring at him with bright eyes as it demolished a pinecone. Hank stood and stretched, groaning as pain shot up from a rock that had dug into his spine. The squirrel chittered and flung the rest of the pinecone at his head.

Hank reached for the pot of coffee they’d left to brew overnight on a flat rock in the fire. He poured a cup and took a sip, it was acrid but warm. He crossed to the other side of the fire and held the cup under Barney’s mustache. After a moment, Barney snorted, shuffled in his sleep, and his eyes popped open. He sat up as Hank walked back to the other side of the fire, set his tin coffee cup down, and packed his bedroll. Barney crab-walked to the fire and poured himself a cup. He was balding, with a large handlebar mustache, his face darkened by days of beard growth.

After a quick breakfast, they loaded the mules and returned to the trail. Barney led Bertha, while Hank guided Jim with the cart. The cart held enough supplies to last a winter — Hank’s insistence over Barney’s protests of extravagance. But Hank had always led, and Barney had always followed, and that was true long before the war.

They walked the Mullan Military Road, cut by Mullan and his crew less than a decade earlier. Though thousands crowded this route at times, it was quiet this year. Near noon, both mules snorted and grew restless. A horse approached from ahead to the west. Without speaking, the brothers moved to the trail’s edge and steadied the animals. The Mullan Road was safer than most — unlike the Bannock Road, where more than a hundred murders had taken place last year — but desperate men wandered the West since the war’s end. Caution ruled every encounter.

Hank and Barney passed a few travelers in either direction and made sure even the hard men gave them space. They’d seen plenty of action in the war and weren’t easily intimidated. Both carried well-used Colt Army revolvers, worn openly and well maintained. Their dress marked them as former soldiers, though they didn’t display Union colors as some did. In the wilderness, a former Confederate who hadn’t let go of 1865 might be easily provoked. Still, their Army revolvers were a clear signal that they had once served the Union. More often than not, ex-Confederates carried Navy revolvers.

Hank pulled his new Winchester Model 1866 rifle from the rifle scabbard mounted to the front of Jim’s cart. Barney drew his scattergun from its place on Bertha. They kept both barrels aimed at the ground. A few minutes later, a man rode up, slowed his horse, and stood off twenty feet up the trail. Seeing that Hank and Barney were well-armed and ready, he slowly took his hand off his sidearm and politely showed his hands.

“Howdy, friends,” he said. “Road clear ahead?”

Hank met his eyes and gave a single nod. “Been a good stretch from Missoula Mills. Not much mud. No trouble.”

The rider nodded back. “Quiet here, too. Bit of mud in the lowlands. I passed some Nez Perce horse traders near Lake Coeur d’Alene — they were peaceable. Spent the night at the Cataldo Mission. Padre was friendly, he gave me a free warm meal and a clean bed.”

“Much obliged,” Hank said. “You get down that way, stop in on Frank Worden in Missoula Mills. Fair trader. Keeps good stock.”

The man tipped his hat and edged past them. “Good luck to you.”

The Mullan Military Road had been a godsend. After crossing Lookout Pass yesterday, they knew this morning they’d leave it behind for two days of hard hiking into the mountains. They’d counted miles from the pass, watching for a campsite marked with a hidden cart-wide trail heading north. Near mid morning they found it, a tree marked above head height with an underlined double X and an arrow pointing the way. Barney checked their father’s pocket watch, it was just before ten o’clock. With no one in sight and the morning having been uneventful, they watered the mules and left the road.

The trail barely took the cart. Sometimes they pushed from behind; other times Bertha helped Jim pull over tangled roots, rocks, or through patches of mud. Tall trees closed in as they followed Nine Mile Creek deeper into the mountains. By late afternoon they reached a fork, where past travelers had left a fire pit and a flat spot for camping. They settled in for the night.

Hank woke Barney in his usual way — waving coffee under his nose. The air was cold but clear, and the dew wasn’t too bad on their blankets or gear. They’d staked the mules in a grassy patch the night before. The animals had grazed contentedly, and the creek ran close enough for the animals to drink their fill. After gathering up their gear, the brothers ate cold beans from the night before and started uphill.

By noon, they had crossed two mountain passes, still dotted with snow, and continued following creek beds and gulches toward their destination. That evening, they camped on the banks of the Coeur d’Alene River.

The river churned with snowmelt. The cold struck like a knife when they crossed, stealing breath and burning skin. Even the mules shuddered, steam rising from their flanks as they climbed out. They tracked east along the bank, boots squelching, until the trail demanded another crossing.

A few miles later, they found the small tributary marked on their map and left the Coeur d’Alene. After another mile, they took a hard left, climbing again into the mountains along another branching creek. Despite the freezing crossings and the sweat that followed, they made good time. The trail rose steadily, and the ground turned dry and sandy.

After a few miles of hiking they found a small tributary creek Joe had marked on their map and turned left into the mountains. The ground grew drier and sandy. They entered a ghost forest where fire had swept through. The lower trunks of the pines were scorched black, and the underbrush had burned away. Passage was decidedly easier here, though the air still held the memory of flame, and their boot soles soon blackened with ash. New growth pushed through the charred soil — like tiny, green fingers reaching for light.

In the mid-afternoon, the forest changed. Ancient cedars rose around them, their massive trunks like church columns. Shafts of sunlight pierced the canopy far above, casting golden pools on the cathedral floor. The air was still, heavy with the scent of cedar bark. Their voices dropped to respectful whispers, as if they’d entered a sacred space.

They continued to spot the underlined XX marks with arrows and knew they were still on track. One mark read: XX 3 Mi. They forged ahead, and soon the trail leveled out, opening onto an acre of cleared, flat pasture. A rough pen stood to one side, holding several donkeys and a mule. Beyond it stretched a flat meadow, about a mile long and curving out about a mile wide, before the mountain rose again.

The trail ended abruptly at a graveled outcrop. Hank’s breath caught as the land fell away before them — revealing a ravine that plunged easily 100 feet to a ribbon of silver water. To their left, the mountain face rose sheer and towering, a fortress wall of stone sparsely dotted with firs clinging to the near vertical cliffside.

Across the chasm lay something extraordinary: a hidden valley cupped in the mountain’s palm. Spring-fed streams laced across the meadowland, catching the afternoon light before cascading into the ravine in delicate falls. The cove of land stretched two miles wide and deep, a perfect amphitheater of green bounded by granite peaks.

The isolation was complete. No trail led here except the one they’d followed. No eyes had seen this place save those Joe had trusted with his secret. Hank felt something shift in his chest — not peace, exactly, but possibility.

Two cabins stood down in the valley beside separate creeks, set back about a half mile from the ravine’s edge. Near one, a man bent over a sluice, working his claim. Barney put his fingers to his mouth and whistled, sharp and loud. The man straightened, shading his eyes, then waved. He rang a small bell, its sound carrying faintly across the open air as he signaled the other cabin.

While they waited, they dropped their packs and unloaded the mules, releasing them into the pen with the others. The new animals and old exchanged brays and snorts. Hank now understood why Joe had asked for some of the items on their list — especially the pulley system and baskets, clearly meant for shuttling gear across the ravine.

A few minutes later, Joe appeared on the far side and hailed them with a shout. They called back, grinning, and watched him scramble across the rope bridge — though Hank felt “bridge” was too generous a word for the contraption.

Joe hugged them both in his bear-like grip. He was a big man: barrel-chested, thick-bearded, with shaggy brows and arms like stovepipes and hands like shovels. He’d grown up with them in the same neighborhood, fought beside them in the war, and now stood beaming at them. He was almost as excited to see the new pulley system they’d brought.

“I reckon you fellas’ll take to this place right quick,” he said. “One of the prettiest spots I ever laid eyes on. Weather’s holding nice! But this basket rig — hell, this is going to change everything.” He slapped Hank on the shoulder. “You should’ve seen me the first time I crossed this ravine. Throwing a rope and a hook like a damn fool, praying to snag a tree on the other side!”

After a few minutes of catching up, they agreed to stack supplies from Bertha and leave the cart loaded while they crossed over to scout for a claim and a place to build their cabin.

That evening, they met Tom and Rick, the miners from the other claim, and all five of them shared a dinner of venison steaks and potatoes baked in the fire. Joe had been here a full year now, and had invited Tom, Rick, Hank, Barney, and two others who hadn’t yet arrived. So far, they had found plenty of garnet, a few small gold nuggets, several pounds of gold dust, and even some silver.

But as they spoke, Hank noticed the tightness around Tom and Rick’s eyes when discussing the yield. Joe and Barney were cut from the same cloth — optimistic, always chasing the next adventure. Tom and Rick were more reserved, their smiles thinner when they spoke of what they’d pulled from the ground.

After dinner, Joe, Tom, and Rick retired to their cabins, and Hank and Barney settled in by the large group campfire. Joe had spent the evening pointing out good spots for them to set up camp, and Hank did his best to temper Barney’s enthusiasm without dampening it. They had plans to reinforce the rope bridge and set up the new pulley system for supplies.

As Hank crawled into his blankets, he felt a spark of real, contented excitement — the first he’d known since the journey began.

I I I I

Tom looked at Hank incredulously. “How in tarnation did you manage that?”

They’d just finished building a much sturdier bridge, lashing rope and wood into place, and incorporated the new pulley and basket system Hank and Barney had brought. All morning they had fought to get the tension on the lines correct, struggling to get the rig stable, all the men bickering and arguing, until Hank finally lost his temper. He told them to take a walk and leave him to it. Tom and Rick had started to argue, but Joe and Barney gave them a funny, quelling look and suggested they give him room. When they returned an hour later, Hank had figured out how to tighten the tensioner and gotten the pulley running smoothly. He only smiled at Tom’s question.

“Well, gentlemen,” Rick said, “I reckon we’ve earned ourselves a soak in a hot bath.”

Barney laughed loud and sarcastically. The three veterans of the plateau traded a glance. Joe grinned. “Oh, you lads are in for a treat.”

The five men walked about a mile inland, toward where the mountain rose steeply and the ground turned rocky. Tall grasses blanketed the flats, broken by thickets of wild rose and scattered juniper in a few varieties. They followed a faint path, climbing flat rocks that formed a rough staircase, and turned past a clump of bushes.

A steaming pool emerged from the shadows. It was fed on the far side by a spring that spilled from a cleft in the rock face, vapor rising all around in wisps and plumes. Sunlight pierced the mist, casting rainbows against the stone. The air carried a pleasant metallic or mineral smell.

“You’re joshing,” Barney said, staring. “That’s a hot spring?”

“As sure as the sky’s blue,” Joe said, grinning.

Without hesitation, Joe, Tom, and Rick peeled off their boots and clothes and plunged into the water, whooping and carrying on. Barney followed with a laugh, jumping right in. Hank, slower and smiling, waded carefully into the steaming pool. Barney let out a deep sigh as he submerged, and Hank groaned in appreciation as the warmth soaked into his bones. The water was hot, but not scalding — just right.

The five men laughed and drifted into an easy silence, letting the spring work its magic.

“It’s a wonder this doesn’t reek of rotten eggs,” Hank said. “Most hot springs I’ve been to reek of sulfur — this one doesn’t smell foul at all. Kind of brisk. Like iodine.”

“Splendid, ain’t it?” Joe grinned. “Got me through the winter out here. I built a little shed over yonder for a winter bedroom. Took it apart once the snow melted to add onto the main cabin.”

“Stayed warm enough to dip in all winter?” Barney asked.

“Yes, sir, it did — just as warm as it is now,” said Joe. “You’d be amazed how many critters it draws. This region’s thick with birds year-round. Rabbits, foxes, even mink. One morning I woke up to a herd of bighorn sheep drinking on the far side. Come winter, they all gather here for the warmth. It’s quite a sight.”

The men sat in the warm water for a while, and Hank looked up at the mountain towering above them. About a thousand feet up, he spotted what looked like the entrance to a cave. For a moment, he thought he saw a person standing there — but when he blinked, it was gone.

He asked, “What’s that opening up there, Joe? Any idea?”

Joe looked up. “I’ve noticed it too,” he said, “but I’m at a loss.”

Hank leaned back in the water, eyes still on the spot, wondering what wonders this place had yet to reveal.

The next morning, he and Barney ferried their supplies across the ravine and laid out the location for their cabin — close to the bridge and not far from fresh water. They marked the site for their outhouse, carefully placed downstream and downwind. Joe had made several trips to Missoula Mills before their arrival, hauling enough lumber for two additional cabins. With that on hand, all they needed was a foundation of loose stones, gathered from nearby.

A week later, their one-room cabin stood finished — two bed frames inside and the small stove they’d hauled in the cart for cooking and heat. The privy took another day. After that, they were ready to begin mining.

I I I I

Hank and Barney stood ankle-deep in the icy creek behind their cabin, panning for gold. The sun warmed their backs as they joked back and forth. Hank’s stomach growled, thoughts turning to lunch, when he spotted a rock that looked like it held silver ore.

“Barn, pass me my knife,” Hank called out.

Barney plucked the knife from the creek bank and tossed it in a lazy arc. Hank caught it cleanly, but the scabbard slipped free. The blade bit deep into his thumb, straight to bone.

“Damnation!” Hank cursed and squeezed his thumb in his left hand, and pulled it against his chest. Blood seeped between his fingers, dripping into the clear water. His eyes squeezed shut against the pain.

“I’m so sorry, Hank. I shouldn’t have thrown it. Let me see.” Barney splashed over, and Hank slowly released his grip to show him the cut. As he did, blood welled out of the deep slash.

They retreated to the cabin where Barney stitched the wound. The needle pierced tender flesh with each careful pass.

“Maybe ease off the panning till this heals up,” Barney said, tying off the final stitch.

“Fiddlesticks. We’ve got a lot of mining to do here, I’ll be fine,” Hank said.

For the rest of the day, Hank favored his right hand but kept panning. The specimen rock he’d wanted to test had tumbled away in the creek’s current, lost among countless others. Over the next few days, he pushed himself harder, especially when Barney inquired about the wound. On the fourth morning, his hand trembled as he tried to sip coffee, splashing it down his shirt front. He jerked his hand away, spilling more. He swore under his breath and his lips pulled back from his teeth in a rigid grimace. When Barney examined the cut, angry blisters dotted Hank’s arm and hand. The wound itself glowed an ugly red.

Within hours, Hank’s neck stiffened and ached. Barney recognized the signs from his darkest war memories. Hank’s muscles betrayed him, twitching and knotting beneath his skin like ropes drawn too tight. The spasms began as small tremors, then escalated into waves that wracked his entire body. His jaw locked shut, teeth grinding like millstones in the cabin’s oppressive quiet. Each ragged breath scraped through clenched teeth as Barney watched, helpless.

The next two days brought fresh torment. Between spasms, Hank caught his breath and met Barney’s eyes. Fear mingled with grim acceptance.

“Nothing to be done now, Barn.” The words came clipped, forced through a rigid jaw. “Seen it before. Just have to see it through.”

“Don’t say that,” Barney’s voice cracked. “We’ll find a way. I swear it.”

But the lie tasted bitter. His mind flooded with memories of field hospitals — the sound of men dying from tetanus — their bodies twisting like branches in a storm. Now those same spasms tortured his brother.

Barney rummaged through their supplies, frantic. He recalled old remedies whispered in hushed tones by desperate soldiers: a poultice of herbs, a concoction of whiskey and honey — anything that might offer relief. He tried what he could, applying warm, wet cloths to the wound, forcing remedies between Hank’s clenched teeth, bought from roadside carts on their way west. But the spasms continued, relentless and unyielding.

The other men came by over the next couple of days, sitting with Hank for a while, until things grew so bad that Barney had to send them away at Hank’s request.

Barney was working on another poultice at the stove when Hank called out, teeth chattering.

“Barney, sit with me. I don’t want to be alone.”

Barney left the stove and dropped to his knees beside the bed, clutching Hank’s hand. The skin was clammy, the grip weak.

“I’m here, Hank. I ain’t leaving.”

As the hours passed, Hank’s body betrayed him further. His neck arched back under a cruel, uncontrollable force. Muscles strained against skin. Barney watched in silent anguish as the spasms rolled through him.

Now and then, Hank’s eyes would find Barney’s, and he’d offer a tight smile — a flicker of his old self breaking through the pain.

“Remember those nights in Chicago?” Hank whispered hoarsely. “We’d sneak up to the rooftop of that old tenement? Thought we were on top of the world, looking out over the city.”

Barney chuckled softly, eyes misting. “Yeah. We fancied ourselves kings. Silly fools we were.”

“Still fools,” Hank said, his breath catching as another spasm hit. “But we had good times, didn’t we?”

Night settled in, the cabin lit by the soft glow of lantern light. The room smelled of sawdust and sweat. Barney kept vigil, heart heavy with what he knew was coming.

The spasms worsened. Hank’s body arched off the bed, muscles tightening to the point of tearing. Barney held him through each wave, murmuring words of comfort — though they rang hollow, even to his own ears.

Hank opened his eyes after a particularly bad spasm. Terror filled, his gaze darted around the room, and in a small, childlike voice he whispered, “I don’t like this. I don’t like this.”

Then his body seized in the most violent spasm yet. His back arched, stiff as a board, only his heels and head touching the mattress. There was a loud crack — the sound of bone shattering — and suddenly Hank went limp, collapsing back onto the bed. Barney gripped his brother’s hand, feeling life slip away beneath his fingers.

His heart stuttered. He cradled Hank’s hand to his cheek as he lost all composure, sobs racking his chest, his own body echoing Hank’s final spasms. Tears came freely now. He held Hank’s hand to his forehead, to his lips, to his face, over and over — unable to let go.

Time paused. The world fell away into a tunnel of blackness. All that remained visible was Hank’s hand, framed in the small aperture of Barney’s grief.

When he finally rose, Barney was spent — exhausted and numb. He covered Hank’s body with a blanket. The sobs had dwindled to stuttering, involuntary breaths, like a toddler recovering from a tantrum.

He staggered to the door, stepped outside, and sagged down on the rough bench Hank had made for them, and the world began to come back. The morning sun bathed the valley in golden light. The wind whispered through the trees.

Jack Seeley shouldered his way from his Uber toward the entrance to LAX’s Terminal 4, dodging rolling bags and distracted travelers staring at phones. The air carried hints of burnt coffee and jet exhaust. A flash of white caught his attention — a man in an immaculate linen suit leaning against a pillar, watching him across the crowd with unsettling focus. He was short and lean, with wild, auburn hair escaping from beneath a white Panama hat trimmed with a black band. His handlebar mustache dominated his face, giving him the air of a riverboat gambler. A long, brown cigarette dangled from his fingers, releasing sweet-smelling smoke that seemed to hover around him rather than dissipate on the breeze. He watched Jack through squinted eyes as he smoked.

As Jack approached the man, a woman in front of him suddenly tripped and fell, sprawling headlong onto the pavement, dropping her rolling bag and the handbag strapped to the handle. Both Jack and the man rushed over to help her, Jack on the right, the man in the white suit on her left. They helped her to her feet and despite a bloody palm, she seemed okay. The two men handed her the bags, and she was on her way. Jack noticed that not only was the man wearing a pristine, white linen suit with shiny, black shoes, he was wearing a white linen vest under his suit jacket. In addition, he had a gold pocket watch chain linked to a watch pocket in his vest. In the maneuver to rescue the young lady, the man hadn’t once let go of his brown, sweet-smelling cigarette.

The man tipped his hat with theatrical precision, then walked away without any luggage or apparent purpose. Jack filed the odd encounter away and headed for security.

After Jack made quick transit through the PreCheck line and made it to his gate, he noticed that the man was also waiting to board. As these coincidences sometimes work out, he turned out to be sitting right next to Jack in first class. After they both were seated, the man turned to Jack and said, “Hello there, my fellow traveler and rescuer of damsels in distress. My name is Sinclair Lipson,” and he paused before adding, “the third.” He had a strange, old-fashioned pacing to his speech and an accent that fell somewhere between Yosemite Sam and a third-tier nightly newscaster. He extended his hand, and Jack shook it dutifully.

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Lipson, I’m Jack Seeley. What brings you to Spokane?”

“Ah, Jack, a pleasure. I’m returning to the area after a long absence. I haven’t been back there in what feels like… well, forever.”

Lipson smiled at Jack in a sort of friendly way, but his eyes were narrowed. His smile was all in the mouth, his eyes looked cold. It gave Jack a chill. He had been about to tell this man that his father was also a ‘Trip’, or third son with the same name, but he thought it better to disengage.

Jack did the universal trick of the frequent flier; he smiled and he reached into his bag for headphones and a book. He pulled out a copy of Hugh Howey’s newest novel, slipping on the Nura noise-canceling headphones that he preferred. Lipson asked the flight attendant for a Jack Daniels on ice, and the flight went smoothly. Lipson consumed several drinks during the flight to Spokane.

I I I I

Jack gratefully grabbed his latte in the Spokane airport before continuing his walk to the car rental to drive through to Kellogg. It was early March, and he had gotten a call from his grandmother’s caregiver, Amy, that he should make the time to come out. His grandmother was unable to walk, even with the walker she’d used for the last fifteen years. She was now effectively bedridden.

Jack asked the cheerful woman at the Enterprise office for something with all-wheel drive and clearance. An hour later, he pulled off the highway and found his way by memory to his grandmother’s house at 621 Chestnut Street. Jack pulled into the driveway of the tiny bungalow. His great-grandfather had built it in 1910, and a cornerstone on the left side that marked it as one of the oldest houses in town. Jack was relieved to see that the yard was in good shape. He’d been paying for a yard service on his grandmother’s behalf since she was unable to take care of the property. The modest homes around it told the story of the neighborhood — some showing pride of ownership with fresh paint and tidy yards, others defined by rusty cars and peeling siding.

Jack’s great-grandfather had died in an accident in the mountains, and his grandfather had been gifted the house upon his return from serving in the U.S. Army during World War II. Jack’s father had been raised in the house until he left for Seattle in the 70s to work as an engineer at Boeing.

His grandmother, Audrey, had been younger than his grandfather, John Jr.; they’d met at a dance for soldiers returning from the war. John had been sent to Fort Lewis upon his return, outside of Tacoma. His grandmother had grown up in Tacoma, and the USO frequently held dances for soldiers on the base. Jack’s grandparents often talked about love at first sight and how they had hit it off immediately. They’d gotten married all in a rush when she was only seventeen. Jack’s father was born in 1946. Jack remembered how his grandfather would scoop him up when he was small. His grandfather always smelled of aftershave. He was always clean shaven, but in the evenings, his face would have a rough stubble of beard.